When Readers Listen is a collaboration between Callie Feyen & myself, in which we challenge ourselves to really listen to a podcast and take something away from it.

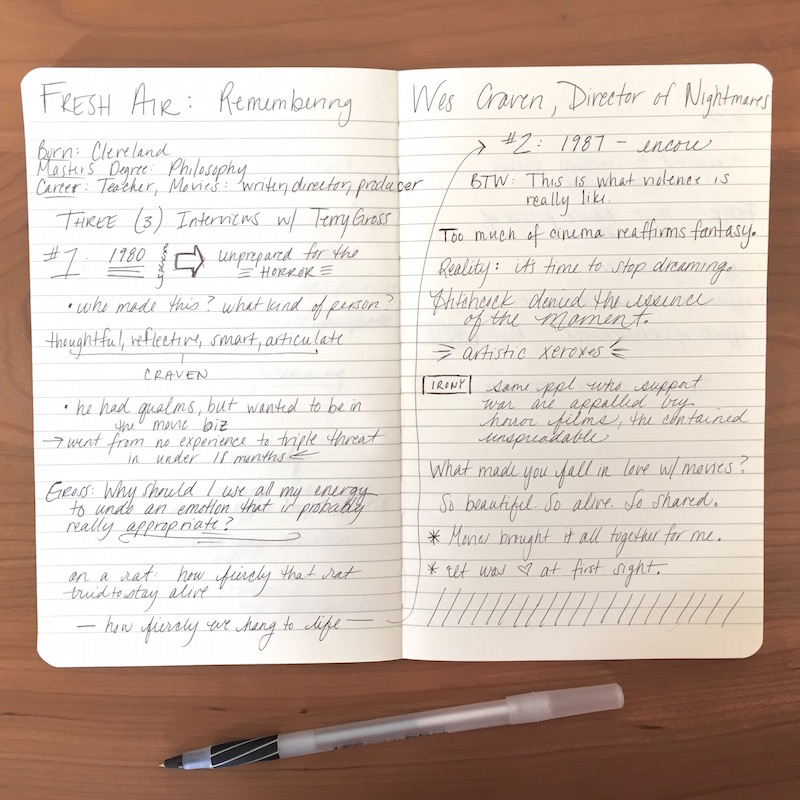

This months podcast is from NPR’s Fresh Air: Remembering Wes Craven.

It’s October, the month of the spooky and scary. I don’t really buy-in to Halloween. I don’t do ghost stories, I’m not a huge fan of dressing up, and I certainly don’t watch horror films. It’s not my thing. Callie, on the other hand, spent many a sleepless night as a kid because of horror movies, specifically those created by Wes Craven. Her essay is 200% worth clicking over to read. It’s about fear and courage and learning to empathize with dark things – as she “finds what shimmers when [she’s] afraid of the dark.”

I cannot remember ever seeing a horror film, really. I tended to look at them as low-brow, unintelligent, and created solely for making money from another Hollywood cash cow. My approach to this podcast was much more academic, and I found myself intrigued by Craven’s approach to the genre – I would never have though there was so much philosophy that goes into a horror film.

Craven is responsible for the Nightmare of Elm Street and Scream franchises, neither of which I have ever seen. I went into this podcast blindly, knowing nothing about the films and nothing about Craven, other than he had recently passed away. Terry Gross at NPR had the chance to interview Craven on three separate occasions throughout his life as a movie maker, and this episode of Fresh Air is a compilation of those interviews.

Interview #1: 1980; following Gross’s viewing of “The Last House on the Left,” Craven’s first feature film and an experience that led Gross to ask the question: What kind of person makes a film like this?

Throughout their discussion, Gross finds Craven to be smart and articulate, and expresses her desire during the film to become non-reactive – to essentially detach herself from what was happening on the screen. Then she changed her mind.

And I figured, well, why should I use all that energy to undo an emotion that’s probably really appropriate? I mean, I figured it was probably appropriate to really be horrified at what I was watching.

Craven agrees with her, and goes on to tell his own story of childhood, when he had to kill a rat and his remembrance that the rat struggled so hard to stay alive. He knew that in his own films, killing couldn’t be stylized or happen off-screen: it needed to be true. His argument was that as a culture, we were becoming desensitized to actual violence – reports from the Vietname war were showing graphic bloodshed while families ate dinner and no one reacted. He wanted people to react.

Interview #2: 1987; “Let’s stop violence that is entertaining.”

What is the benefit of horror that is actually played out on screen, versus the antiseptic horror the entertainment had become used to?

Craven: I think the benefits of seeing that is that it reaffirms reality rather than reaffirming a fantasy. Too much of American cinema dealt with reaffirming fantasies… And my feeling was, it’s time to stop dreaming. And I guess that’s become the theme of my entire work – it’s time to wake up.

In the interview, Craven exposes the irony of people shunning him for his work, while supporting an actual war going on in real life.

I always found it an irony that, you know, the same people that would support a war or, you know, live a lifestyle that would require entire third world countries to be put in near-slavery would, at the same time, be appalled by somebody that did something that was only effective within a certain closed, dark room called a movie house. It was very interesting.

Interview #3: 1998; Craven as Hybrid Horror + Satire

Craven’s larger body of work is known for satirizing the very genre that it is, and as Craven says, it was a way to acknowledge the history of sexism and plain stupidity inherent in the genre:

You know, there’s all those cliches in horror films that, you know, we wanted to avoid and also acknowledge or stand on their head.

Gross & Craven also discussed how horror films seems to be a way for the culture at large to deal with fear outside of themselves: so many films were made about the effects of science because people didn’t know how to feel about the atomic bomb and other scientific advancements that seemed to come with a hefty price tag.

My Takeaways

- People are not always what they seem – even horror film directors.

- We should pay attention to when we decide to neutralize our reactions. What is going on that we don’t want to admit is real?

- We should allow ourselves all healthy reactions: to horror, to sadness, to joy. We should feel these things because they are there to feel.

- The act of watching a movie is a shared experience: the ability for dozens of humans to experience the exact same story is a powerful thing. I think this also applies to books, music, and visual art: anything that tells a story.

Are you a watcher of scary movies? If so, what motivates you to go?

And if you’ve listened to the interview, what did you think?

And don’t forget to check out Callie’s thoughts as well over at www.calliefeyen.com!

Leave a Reply